Palača Belgramoni Tacco, Piano nobile (prvo nadstropje)

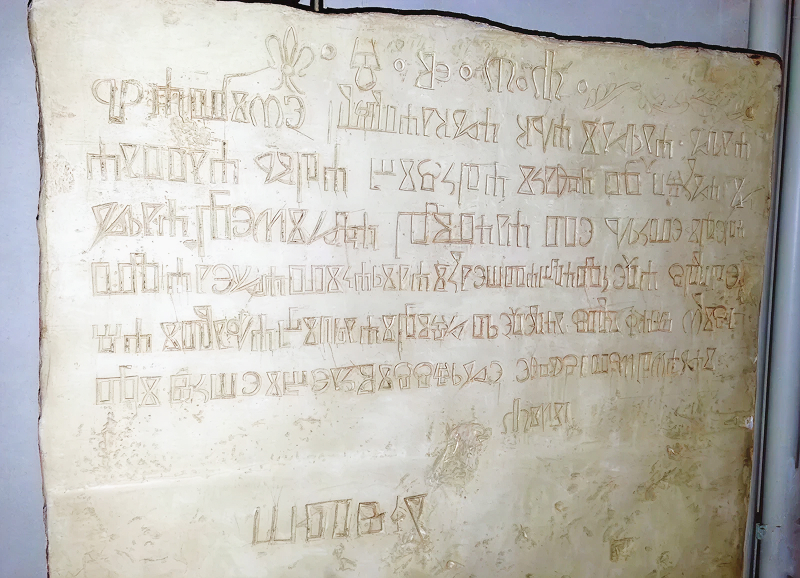

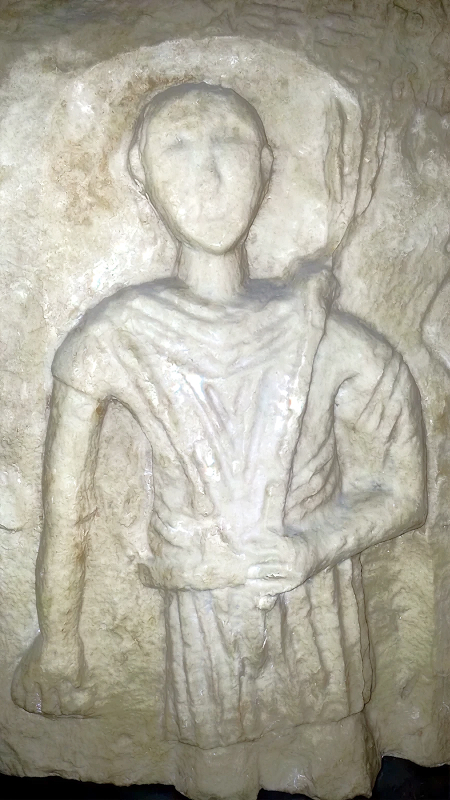

V 15. stoletju smo v Istri priča preoblikovanju zapuščenih in siromašnih področij s številnimi votivnimi cerkvami. Gradnje in opremljanje srednjeveških cerkva v Istri so bile vezane na naročila potujočim delavnicam zidarjev, kamnosekov in slikarjev, ki so jih že vodile družine mojstrov s pomočniki. Velik zagon v ljudskem umetniškem oblikovanju pomeni delovanje glagoljašev Tretjeredcev, ki se naselijo v Kopru in prinašajo okoliškim vasem evangelij. Vklesana glagolska posvetilna besedila opremljajo tudi vidnejše hiše veljakov. V zaledju obalnih mest so se ohranili nekateri izjemni poznosrednjeveški izdelki, ki so plod spontanega ljudskega izraza, s podpisi avtorjev. Kamnoseška tradicija v pretežno kraški istrski pokrajini in dekorativno oblikovanje v kamnu je ena od stalnic ljudskega hotenja pri obdelavi trdega apnenca. Glagolska epigrafika se v teh prostorih pojavlja od enajstega stoletja dalje. V skopih besedah obeležuje trajne zapise, dejanja in samozavest elitnih slovanskih skupnosti ter posameznikov. Staroslovanska pismenost, ki jo dolgujemo poslanstvu Konstantina Cirila in njegovega brata Metoda na Moravskem v devetem stoletju, ni omejena samo na podeželske prostore ali liturgični jezik. V fevdalnih sredinah in nato tudi v mestnih okoljih postane jezik uradnih dokumentov. V mestnih arhivih se hranijo listine, napisane v glagolici, kjer so zabeležene donacije, pogodbe, zapuščine in drugo.

Glagolska kultura izoblikuje tudi literarni jezik. Benetke, ki postanejo središče evropskega tiskarstva močno vplivajo na nastanek istrskih prvotiskov, med katerimi zavzema posebno mesto Glagolski misal iz leta 1483, ki se hrani v Ljubljani. Bogato simbolično in pripovedno izročilo svetih besedil se prepleta z ljudsko teologijo in ikonografskimi predlogami, ki odsevajo agonijo civilizacije v »jeseni« srednjega veka in napovedujejo skorajšnji versko-duhovni in moralni razkol renesančne Evrope. V domačih delavnicah zasledimo samosvoje vzorce v okviru klasične krščanske ikonografije. Mojstri vešče obvladujejo kamnoseško kladivo, slikarski čopič ali dleto.Veliki svetniški slikarski ciklusi, ki se pojavljajo že v 2. polovici 14. stoletja, se v cerkvi sv. Štefana v Zanigradu manifestirajo z velikimi poslikanimi ploskvami, ki si sledijo kot moderen strip. Župniki in drugi naročniki sestavljajo slikarske programe z izvirnimi sporočili. Kot idejni tvorec in kasneje razlagalec posamezne vsebine postaja glagoljaški kler pomemben nosilec kulture in vzgoje v življenju skoraj nepismenega ruralnega okolja.

Cerkvica sv. Trojice v Hrastovljah je edinstven spomenik srednjeveškega slikarstva na naših tleh. Grajena kot miniaturna troladijska bazilika ohranja na notranjih poslikanih površinah ime mojstra Ivana iz Kastva, ki v času velike evropske renesanse ustvari ciklus fresk kot epski zapis ruralne srednjeveške ljudske teologije in življenskih spoznanj. Površine fresk so tudi poseben arhiv dokumentov, ki jih v ploskve vgrebejo naključni obiskovalci z ostrim predmetom: latinski in glagolski »zgrafiti« prinašajo sporočila o naravnih nesrečah, priprošnjah, pomanjkanju, ceni žita in drugem.